China Country Page

China

Production

Cotton is planted in China from April to June and harvested from September through December. Broadly speaking, there are three large-scale growing areas:

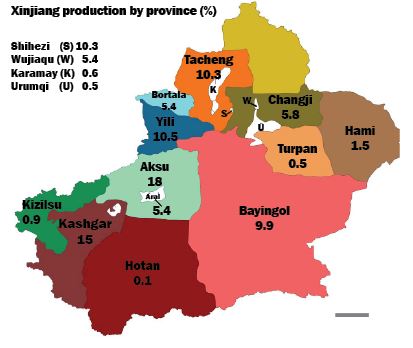

- the increasingly dominant western region of Xinjiang (accounting for over 90 percent of national output);

- the traditional northern or Huanghe River (Yellow River) Valley region (including “Jiluyu”, comprising Shandong, Hebei and Henan);

- the southern/central area located around the Yangtze River and its tributaries.

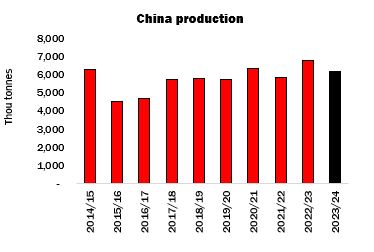

According to Cotlook’s data, Chinese cotton output peaked at around eight million tonnes in the 2007/08 and 2008/09 seasons, before changes in government policies resulted in a sharp decline to below five million tonnes by 2015/16. A strong recovery has been evident since 2017/18; national production exceeded six million tonnes in 2020/21, and has remained at roughly that level since.

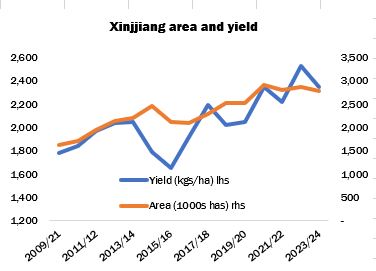

Yields have also improved markedly, to reach over 2,200 kilos per hectare in 2022/23. As yields improved, cultivated area has fallen; from a high point of almost six million hectares in 2008/09, the area planted to cotton has fallen to less than three million ha.

Xinjiang remains the focus of government support for cotton production (around a decade ago that region’s share of national output was only roughly 40 percent). A target price system was implemented in Xinjiang in the 2014/15 season, offering subsidies to growers based both on the area cultivated and the level of production, including, in the latter context, a premium for long staple varieties. (Other regions were excluded from the regime but instead received a direct subsidy.) In 2015/16, the area provision in Xinjiang was dropped, apart from in three specific districts producing long staple varieties in the south of the region. The subsidy based on production remains in place.

The impact of the above changes on long staple output was huge: having fallen to a low point of 35,000 tonnes in the 2013/14 season, the figure in 2015/16 rebounded to a couple of hundred thousand tonnes. This led to oversupply, and a consequent sharp reversal in long staple output during 2017/18. The volume produced remained relatively low in the subsequent few seasons, but has risen recently owing to record prices; in 2022/23, long staple output in Xinjiang was in the region of 75,000 tonnes.

Consumption

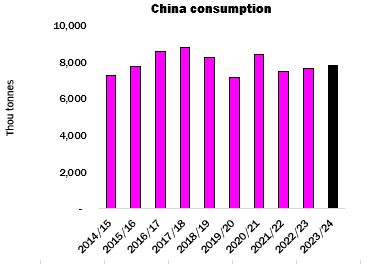

China is the world’s biggest consumer of raw cotton, having accounted for over 30 percent of the global total in recent seasons (32 percent in 2022/23). That figure is down from a recent peak of over 40 percent in 2007/08, when Chinese consumption reached 10.5 million tonnes. Since that high point, consumption in the country has fluctuated between around 7.5 and 8.5 million tonnes, depending largely on price levels vis-à-vis competing fibres, and conditions in the downstream market.

In the late 1980s, China’s share of cotton fibre consumption was markedly higher, but has since declined owing to the increased use of man-made fibres, as a portion of spinning capacity was switched away from cotton.

Cotton imports

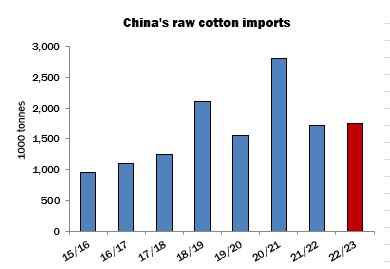

The discrepancy between China’s domestic cotton production, and its consumption needs, also make the country the biggest importer of the fibre. Since the 2018/19 season, seasonal imports have ranged from 1.5 million tonnes to almost 2.8 million.

Following China’s entry to the WTO in 2001, certain import obligations were put in place. For cotton, a tariff-rated quota (commonly referred to as ‘TRQ’), attracting a tariff of one percent, was established for 818,500 tonnes in 2002, rising to 894,000 tonnes by 2004. In 2005, in addition to the WTO commitment, Beijing also allocated some quota on a ‘Sliding-Scale’ of import duty (depending on the contracted CIF price), starting at 5 percent. The Sliding-Scale tariff was adjusted in 2007, by raising the base tariff to six percent and increasing the ‘trigger price’, below which the rate of duty increased, up to a maximum of 40 percent.

In 2008, the Sliding-Scale tariff was amended further, on a scale from 5 to 40 percent if CIF prices fell below the ‘trigger price’, but with a fixed duty of 570 yuan per tonne applicable from the target price upwards, the result being to cheapen, relative to 2007, the cost of imported higher grades. The same rules have prevailed since.

In 2012, the government introduced the concept of a 3:1 Sliding-Scale quota, whereby qualifying mills that buy cotton from the State Reserves are entitled, if quota is allocated, to receive one tonne of import quota.

In 2014/15, with the change in subsidy policy, the government indicated that stricter controls of imports would be applied. In 2015, no quota was allocated beyond the WTO-related TRQ. In more recent seasons, between 400,000 and 800,000 tonnes of Sliding-Scale quota were allocated to Chinese buyers.

Imports may also be conducted outside of the quota system, on payment of the full tariff rate of 40 percent. This has been quite a common feature of business in certain periods, owing to the relationship between local and international prices which meant that imported lots still represented good value, even with the 40 percent duty. However, in recent seasons the Chinese domestic price has traded at a premium to imported cotton and hence imports without quota have decreased dramatically.

The National Development and Reform Commission controls the quota allocation process. Any unused quota must be returned to NDRC for redistribution. Penalties in the form of reduced allocation in the following year may be applied to quota holders that under-use their allocation. Applications for the following year’s quota are to be made each October.

The TRQ is divided into two quotas, one for general trade and one for processing enterprises (whereby goods manufactured from imported cotton must be exported). The processing quota is effectively duty-free.

Cotton placed in bonded warehouses or imported into special manufacturing zones does not require a quota licence until it passes through customs.

The bodies eligible to participate in importing cotton are state trading enterprises, central government organisations with State Reserve functions, enterprises with actual import performance in the previous year and mills with over 50,000 spindles.

Mills in free-trade and special economic zones are subject to special import arrangements.

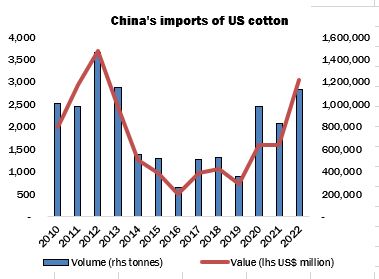

Phase One agreement

In December 2019, following a protracted trade dispute between China and the US, a ‘Phase One’ agreement was reached, which contemplated a substantial increase in Chinese purchases of US agricultural products, calculated from a base year of 2017. (In that year, China imported 505,000 tonnes of US cotton, with a value of some US$980 million.) The agreement was ratified in January 2020 and came into force the following month. As part of the Phase One deal, China promised to buy an additional US$32 billion worth of US agricultural products over the next two years. However, additional details (such as a breakdown by individual commodity) were lacking and how much of a contribution cotton might make to that increase was open to question.

In the event, China’s purchases of US cotton in 2020 and 2021 amounted to more than 1.8 million tonnes, with a value of US$3.2 billion. A further 1.1 million were imported in 2022 (US$3.1 billion).

AQSIQ

In 2008, the General Administration of Quality Supervision, Inspection and Quarantine announced new registration requirements for foreign suppliers of raw cotton, together with a grading system for those suppliers. A registration certificate has been required for imports received from March, 2009 (otherwise, more stringent and costly quality checks are triggered). The grading system envisages placing suppliers in one of three bands: A, B, or C, each of which attracts progressively more demanding inspection criteria.

State Reserves

The State Reserve is used as a macro control tool for the domestic cotton industry. In 2011/12, the government initiated a temporary State Reserve plan, setting a minimum price (for basis Type 328 lint) at which it procured cotton, provided the vendor had bought seed cotton at or above a guide price published by the China Cotton Association.

The government announced a similar plan for the next couple of seasons. In addition, the State Reserves Corporation took up a fair volume of imported cotton.

Auctions in 2012, 2013 and 2014 saw some of the accumulated reserves returned to the market but the government was nonetheless left in control of over 11 million tonnes by the end of 2013/14.

In recent years the State Reserve has adopted a ‘rotation’ policy, which entails an annual auction series to dispose of older stocks (at times sold together in a parcel with more desirable, younger lint, to encourage sales), while buying of both domestic and imported cotton to replenish reserve warehouses is undertaken by state-owned enterprises. In order to ensure a smooth supply for domestic mills, at times only spinners are permitted to participate in auctions.

The very firm local and international prices recorded during 2021 resulted in active buying at that year’s auction series, and by Cotlook’s calculation, older stocks (cotton produced in the 2011/2014 seasons) were virtually depleted by the autumn of 2021. By the end of the 2022 purchasing programme (during which less than 90,000 tonnes was acquired for State Reserve warehouses), total stocks were estimated to be in the region of 2.5/3.0 million tonnes.

No official purchasing programme took place in 2023, while almost 885,000 tonnes were disposed of via the auction series which ran from late July to mid-November. A substantial volume of cotton is thought to have been purchased by state-owned entities on behalf of the Reserve during the 2023/24 season, but by early 2024, the volume in State Reserve warehouses was estimated by most observers to stand below the level considered optimal from Beijing’s perspective.

History of the Reserves

Having peaked in 1984/1985 and subsequently fallen, stocks began once again to accumulate from the early nineties onwards, with the result that they were equivalent to 117 percent of annual consumption by the end of the 1998/1999 season. Sales policy was then directed towards achieving a reduction in the stock burden, which had been accumulated at relatively high prices. The result was quite dramatic and, by 2003, the State Reserves had been depleted. The policy was subsequently reversed, in the sense that new reserves were accumulated, principally in the interests of protecting farmers from low prices. The State Reserve mechanism was once again actively employed during the 2008/09 season, which saw the absorption of an additional 2.7 million tonnes, mostly of Xinjiang cotton, into reserve warehouses (in addition to existing holdings), and the subsequent release of most of those purchases (including old crop) back to the market. The reserves were depleted to virtual exhaustion during the 2010/11 season, as prices rose to record levels, thus reducing the capacity of the state to intervene in the market at that time.

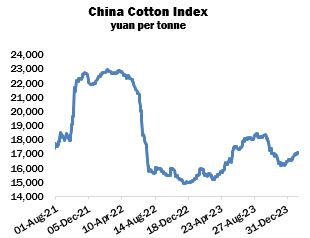

China Cotton Index

The China Cotton Index (CC Index) represents the spot price for Grade 3128B, delivered mill, during the preceding week. It is managed by Beijing Cotton Outlook; delivered mill prices are collected every working day for a range of domestic qualities and an average for each grade is calculated for each province. The ratio of spinning capacity by province vis-à-vis the national total is used to weight the resultant average values. The CC Index is compiled only from the weighted average prices for Types 3128 and 3129 (adjusted by one percent to bring it to the equivalent of a 3128 value).

As well as being a general price indicator, the Index is used as a measure of the value at which banks will accept warehouse receipts against cotton to be sold on the China National Cotton Exchange.

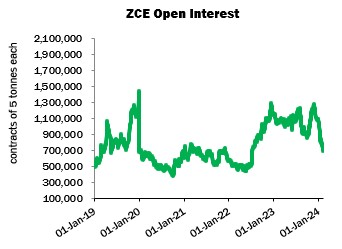

ZCE

The Zhengzhou Commodities Exchange began trading a raw cotton futures contract (No.1 for Type 3128B inland, i.e. not Xinjiang, domestic saw-ginned upland white cotton) on June 1, 2004. Xinjiang cotton was included at a later juncture. The units traded are 5-tonne lots, quoted in yuan per tonne. The months quoted are January, March, May, July, September and November.

ZCE also launched a cotton yarn futures contract (carded 32s single cotton yarn) in August 2017. In contrast to the raw cotton contract, which represents a seasonal commodity, yarn is quoted for every month of the year.

Detailed rules for trading on the Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange can be viewed here: http://english.czce.com.cn

Yarn production

China’s spun yarn output (cotton, man-made fibres and mixtures) has increased considerably since the early 2000s. By the end of 2016, China’s total spindleage had risen to 120 million spindles, and spun yarn production was 18.84 million tonnes. Year-on-year expansion in yarn output has continued, notwithstanding a sharp fall in cotton consumption, according with the rapid pace of investment in the industry.

In an article for Cotton Outlook during June 2019, it was noted by an official from CITIC Futures that the government’s production target was to create a capacity of 20 million spindles in Xinjiang by 2023. In the event, that target was achieved around two years early, with the figure at the end of 2022 standing at almost 22 million spindles. Northern Xinjiang, which accounts for 80 percent of the capacity, is well placed to benefit from the strategic ‘One Belt, One Road’ initiative, which aims to facilitate access from western China to neighbouring countries and beyond.

However, the continued expansion led to a surplus of cotton spindleage in Xinjiang, with the result that spinners have at times been forced to compete for the available fibre, and operate below their maximum capacity. Some mills have scaled down their operations in the 2022/23 season.

History of China’s cotton industry

China’s cotton industry was strictly controlled by the government from the nineteen fifties onward, with cotton planting areas determined centrally in order to achieve a set target of production. All cotton was purchased by the state and distributed according to a state plan. In 1978, rural reform resulted in the establishment of a “production responsibility system”, removing the direct control of government on planting decisions and allowing farmers to make adjustments based on the prices received. However, the government maintained control over trade and farmers were obliged to sell to the state. By adjusting the procurement price, therefore, the government could virtually dictate the level of production but this often resulted in swings from oversupply to under-production. The All-China Federation of Supply and Marketing Cooperatives was designated as the sole cotton marketing agency, responsible for purchasing all production at the set price and for selling onward to textile mills and to the state export agency. Unsold quantities were either bought by the state or remained in the Supply and Marketing Cooperatives’ stocks, creating a financial burden.

Commencement of reform

The first reforms came in the nineties. In 1996, a band in which cotton could be purchased around the state price was established. Secondly, a national “cotton exchange fair” was established, at which cotton could be traded. However, major reform did not happen until 1998, when the set procurement price was replaced by a “guide” price and the Federation of Supply and Marketing Cooperatives was transformed from a department of state into an independent commercial company. From 1999, the monopoly purchasing role of the Federation was broken, with some agricultural and textile departments allowed to participate. Furthermore, the National Cotton Exchange began to function.

In July 2006, a change in the Rules on Quality Supervision and Administration deleted references to ‘relevant permission’ being obtained by those wishing to trade or store cotton (though not for ginning), bringing a further liberalisation of the internal cotton circulation system. A number of international trading companies have since been granted licences and have begun to participate actively in domestic trade. Their involvement has led to a general rise in trading standards.

Chinese organisations

China Cotton Association

A non-profit organisation, funded by members (growers, cooperatives, production enterprises, merchants, ginners, machinery manufacturers, research institutions, local cotton associations, warehouses), by government grants and by income from services. Roles include implementing government trade policy, conducting research, developing and enforcing codes of practice, developing information and technology exchanges and partnership programmes, resolving disputes, protecting the industry’s interests.

State Development and Reform Commission

Aims to develop a balanced policy for the Chinese cotton industry; plans and supervises imports and exports; manages the state cotton reserve.

Ministry of Commerce

Organises and coordinates anti-dumping and anti-subsidy programmes; ensures fair practices in international trade; monitors imported goods and rectifies problems of quality.

Ministry of Agriculture

Oversees cotton production; prepares plans and policies; organises technology programmes.

State General Administration for Quality Supervision and Inspection and Quarantine

Law-enforcement agency under the direct control of the State Council, authorised to implement quantity and quality control on exports and imports and grant certificates.

Bureau of Fibre Inspection

A division of the State Bureau for Quality Supervision and Quarantine with sole responsibility for checking the quality of cotton and other fibres and issuing relevant certificates. Formulates, amends and implements standards.

National Bureau of Statistics

The body responsible for issuing statistics about cotton acreage, production, consumption and cotton yarn output.

All-China Federation of Supply and Marketing Cooperatives

Supervises the cooperatives in purchasing and processing cotton; guides farmers wanting to turn cooperatives into share-holding companies.

China National Cotton Exchange

Under the control of the Federation, the Exchange is a membership-based marketplace for spot and online (internet) trading.

Zhengzhou Commodity Exchange

Zhengzhou was the first commodity futures market (forward contract trading) in China. It opened in October 1990, and initially traded grain. Other futures markets are the Shanghai Futures Exchange, Dalian Commodity Exchange, China Financial Futures Exchange and Shanghai International Energy Exchange.

China National Textile and Apparel Council

A national, non-profit organisation representing different sectoral interests, including the China Cotton Textile Association. Its purpose is to serve as a bridge between its members and government, and provide services to members.

China National Cotton Group Corporation

A diversified national cotton distribution and cotton processing company under the Federation, its operations include purchasing, processing, storage and shipping, brokerage and sales. It also owns an Australian cotton farm.

China National Cotton Reserves Ltd. Company

A state-owned business under central government control, solely responsible for managing the State Reserve, with own storage facilities.

China National Textile Import & Export Corporation

Specialises in cotton import/export and transactions.

Updated February 2024